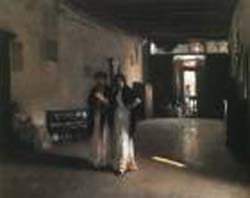

Daughters

of Edward

Darley Boit

John Singer

Sargent -- American

painter

1882

Museum of Fine

Arts,

Boston

Oil on canvas

221.9 x 222.6

cm (87 3/8

x 87 5/8 in.)

Gift of Mary

Louisa Boit, Julia Overing Boit, Jane Hubbard Boit, and Florence D.

Boit in memory of their father, Edward Darley Boit 19.124

Jpg: mfa

/ Jim's

Fine Art Collection

(See interactive

zoom at the MFA)

In 1883 Sargent

exhibited at the

Salon his portrait which he called Portraits d'Enfants or

Daughters

of Edward Darley Boit. Its composition was criticized for its "four

corners

and a void" the children not having any relationship to each other but

the painting, overall, was widely praised. (Charteris, P57-58). The

painting

is large and exactly square, for this reason and it's composition, it

baffled

and intrigued the critics of the day.

When I first saw

this picture I found

it rather odd myself. I felt the girls are curiously isolated from each

other even before I read Charteris's account. The title of the painting

clearly indicates that these are daughters, but it was my first

inclination

that the front two girls must be the daughters -- but what am I to make

of the rear two girls? Why would he paint them in such a fashion? They

are both clearly dressed in very similar clothes, almost a uniform --

could

they be children of servants? The one in profile is almost

unintelligible

as if he was intentionally de-emphasizing the two from us. Why would he

do this? Were the daughters close to the servants? Were they playmates?

Why would they even be included in the picture?

As always (or

nearly so) my first

inclination was almost totally wrong. All four children, it turns out,

are the daughters of Edward Darley Boit. But instead of answering

questions,

for me, it only raised more -- why are the rear daughters so obviously

beyond the foreground of what one might expect of a portrait painting?

Do you feel a sense of melancholy here? I did.

****

Before I answer

these questions (and

I will later) allow me to turn your attention to the artist himself to

see if I can shed light into the mystery of why this composition.

Hon Evan Charteris'

writes in his

biography of Sargent:

I met Sargent

for the first

time in May, 1884, at a party given by Mrs. Henry White at Loseley. I

have

found a record of my first impression in a letter written at the time .

After giving a list of the party it runs: "Also Sargent, who is

interesting

round and about his own subject, though he talks slower and with more

difficulty

in finding words than anyone I ever met. When he can't finish a

sentence

he waves his fingers before his face as a sort of signal for the

conversation

to go on without him -- at least, that is the impression I came after

staying

in the house with him." That impression was modified as time went on,

though

he always talked slowly. He gave the idea of one grasping at words

which

danced elusively in his brain; his conversation was never fluent, but,

like his painting, it could be immensely descriptive. He wasted no

words

-- it may even be doubted if he had any to waste -- but those he used

were

like strokes of his brush, significant and suggestive; indeed he could

convey a weight of meaning by a gesture or a truncated phrase. He could

transpose sense and experiences into words with more character and tang

in his rendering than many more accomplished masters of phrase. When he

talked of matters related to art, or when he was with intimates, he

found

words with comparative ease. Even then there was hesitation, as though

he was at his easel determining the next stroke of his brush. But his

hesitation

was itself often expressive and in any case so characteristic that

certainly

no friend of his would have had it otherwise. So much lay in the back

of

it: such authority, such anxious sincerity, and at the same time, so

much

humor and finesse. No man had more entirely home-made opinions so

wholly

the unadulterated product of his own reflection or experience. His wit

was true and direct, free of paradox, an overflow of his own

personality.

He resembled Henry James, in that nothing would induce him to make a

speech.

More than once at a dinner in early days the shouts of the diners got

him

to his feet, when he would stand struggling with his nervousness,

apparently unable to utter. On one occasion blurting out, "It's a

damned

shame," he subsided into his seat amid a tempest of applause. (Charteris

, P145-146)

****

Edward Darley Boit

(1840-1915) was an

fellow expatriate American Painter and his wife Mary Louisa Boit were

friends

of Sargent. They lived for periods in Boston, in Rome, and in Paris.

Most

likely they met in Paris although it's not known exactly when. It was

in

Paris that he painted the picture. Like Sargent, they were prominent

members

of the American artistic community and therefore shared quite a bit of

camaraderie. It was the Boits, interesting enough, that Ralph

Curtis mentions in his letter

of John visiting the day of "disaster" of his Madame X

showing

-- 1884 Salon, two years after this.

The painting of the

children is in

the Boit's Paris apartment, 32, avenue de Friedland. You

can

see a number of influences that Sargent was working with at the time.

On

his trip to Spain in the late 1870's he studied Velazquez who had a

great

influence on many French painters. Sargent himself copied Velazquez's

Las Meninas of 1656 (Museo del Prado, Madrid) in 1879 and you can

see

the idea of depth, dark  tones

and shading with a source of light at the far distance, and the change

in focus from people at various distances. He also obviously drew

from his earlier work in the Venetian

studies of c. 1880-2, in which he had been "experimenting with the

effects of receding perspectives, shifting focus, oblique light and the

atmospheric qualities of dark spaces . . . ." (Ormond,

P.56) tones

and shading with a source of light at the far distance, and the change

in focus from people at various distances. He also obviously drew

from his earlier work in the Venetian

studies of c. 1880-2, in which he had been "experimenting with the

effects of receding perspectives, shifting focus, oblique light and the

atmospheric qualities of dark spaces . . . ." (Ormond,

P.56)

Although the

towering vases and the

large room seem to dwarf the children, but they did in fact exist "The

vases in the picture, made by the potter Hirabayashi or his workshop,

of

Arita, Japan share the family migratory existence, making sixteen

transatlantic

crossings and suffering repeated damage"

(Ormond,

P.56)

The four Daughters

of Edward Darley

Boit are, from left to right: Mary Louisa (1874-1945, about 8 years old

at the time), Flourennce (1868-1919, about 14 yrs old), Jane

(1870-1955,

about 12 yrs old), and Julia (1878-1969, about 4 yrs old). None of the

girls ever married, and both Flourennce and Jane, the two rear

daughters,

became to some extent mentally or emotionally disturbed. Mary Louisa

and

Julia, the front two girls, remained close as they grew older, and

Julia,

the youngest, became an accomplished painter in water-colors. (Ormond,

P.56)

There was no way

John Sargent could

have know the psychology or what life held for these children when he

painted

them in 1882. Could this have been a fluke-- the way they were

positioned,

the rear daughters detached from us, the one leaning on the vase not

even

looking at us? Maybe. Was he just lucky? Possibly. But it is my

considered

opinion that John Singer Sargent's gift of seeing the world was very

special.

I know, from books,

that he sometimes

chose the clothes for his sitters. I don't know to what degree he

allowed

them to find their own place -- there own buoyancy (there

is no known study of this painting). What I do know, in the paintings

in

which he took great care and did many studies, such as Madame X

and Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, he sketched his subjects in

many

different ways following them like a "snapshot photographer to catch

the

[person(s)] in attitudes helpful to his main purpose" (Sir

Edmund Grosse, Charteris , P145-146).

Vernon Lee writes:

I remember

once asking whether

he was aware of the character of the people he painted; and his denial

of all knowledge of interest in their psychology is surely confirmed by

the very fact that . . . this most reserved and delicately

unmercenary

of artists did make certain portraits of certain sitters, and pocket

the

price, evidently without a suspicion of what he had told about those

who

paid it. That quite unverbal, intuitive imagination of his had fastened

on a the facial forms, the pose and gesture, sometimes even the

accessories,

which revealed the man or woman's character and life. To this kind of

imagination

I would apply Ruskin's adjective penetrative, for Sargent's art

does penetrate to the innermost suggestion of everything he painted,

[and

he] does so by following its merely visible elements. (J.S.S.

In Memriam, By Vernon Lee,

P.253-254)

But unlike Romanticism

or Pre-Raphaelelite

Art Sargent was most Modern, in the truest sense of the word. He

wanted

to convey only what he saw and convey it in the way he saw it.

I do not

think Sargent,

despite the infinite ingenuity he showed in his attempts, was an

imaginative

painter like Watts or Besnard, imaginative in the sense of building up

allegories and narrating events. His symbolism was immanent in the

aspects

which he painted. (Vernon

Lee, P.254)

If

you look at

John Sargent's portraits, I think you can see over and over again, the

personality of the individuals coming through.

No one else could

have painted Daughters

of Edward Darley Boit. The genius of John Singer Sargent is not so

much in his conscious mind or what he does per say but in what

he doesn't

do. It is his unconscious brilliance and sensitivity to his great art

flowing

out from years of training -- a lifetime of painting (from when he was

a little boy) and his special way in which he was so verbally shy. It

is

as if he was a chameleon -- not in the sense of his own colors changing

(for he was so firmly grounded) but in the way, like many great artist

(certainly not all) his weakness (or what we might call weakness

-- his verbal shyness) was possibly a byproduct of, or a contributing

factor

towards his great gift -- that ability to feel an energy of a room, of

a person, of a space, to feel it and sense it to a degree and to a

level

above most of us. It is as if he could feel the subconscious energy of

others (most importantly not disturb it) and transpose it into paint,

onto

canvas -- possibly even beyond his own conscious understanding.

In the hands of a

lesser artist the

composition of Daughters of Edward Darley Boit would have been

ruined

-- it is just too oddly strange. Like the most delicate flower, this

painting's

petals would have wilted instantly in the crass temperament of

pre-conceived

notions. But not here, and not by John Singer Sargent, for this

painting

is truly Penetrative!

Notes

Provenance:

The artist; to

Edward Darley Boit, Paris, 1882; to his daughters, the sitters; to MFA,

1919, gift of Mary Louisa Boit, Florence D. Boit, Jane Hubbard Boit,

and Julia Overing Boit

Exhibitions

John Singer Sargent

Retrospective, 1989-1999

|