|

|

|

Subject:

Who was Coventry Patmore

This was an article in today's Guardian (British respectable newspaper NOT owned by Rupert Murdoch) - I thought it might make a little addition to JSS's portrait of Coventry Patmore, to which the article refers. . . . (Hastings is a rather dull town on the south coast, whose chief claim to fame is being the site of a battle in 1066.) Enjoy! Philip (see

below Patmore starts on paragraph 3)

Note:

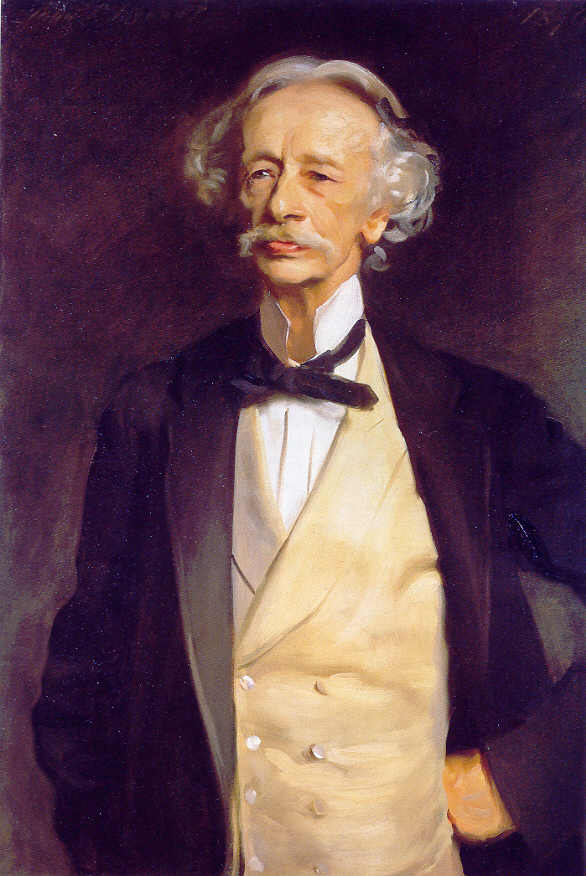

National Portrait Gallery, London |

| Guardium

Unlimited homepage

Elsewhere Honed in Hastings David McKie

Thursday February 22, 2001 A bypass is planned at Hastings, and the ghosts of famous writers and artists who stayed or lived in the town are being mustered to stop it. Ros Coward listed a few in a column last week, including Rossetti, Lear, Lewis Carroll, and Rider Haggard. A reader added Robert Tressell, author of The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists. Reference books suggest many more writers: Byron, Keats, Leigh Hunt, Charles and Mary Lamb, Thomas Hood, George Crabbe (knocked down by a phaeton while crossing a road in the town), Thomas Carlyle and Mary Webb, who died there. Disappointingly, though, few of them seem to have stayed in Hastings for long. The only two long-stay residents here were Haggard and Coventry Patmore. Haggard can look after himself: he wrote She and King Solomon's Mines. But who was Coventry Patmore? The name crops up in almost every anthology of Victorian verse, but the author belongs to that troubling category, people you feel you ought to know about but don't. I suspect he seems to matter largely because of his name. In 19th-century England, children - well, anyway, boys - were named in the expectation of subsequent eminence. If your first name was not entirely arresting, the second came into play. A Conan Doyle. H Rider Haggard. J Meade Falkner. Patmore's father must have named him with that in mind. "Coventry is a clever fellow," his grandmother taught him to say. His father was just as admiring, but spoiled things by getting into embarrassing scrapes. He lost most of his money by unwise speculations in railway shares and had to flee to the continent. While acting as a second in a duel he so far provoked the rival duellist that his champion got shot: he escaped prosecution for murder but again had to flee to the continent. Later he embroiled William Hazlitt in a fearful scandal. His name became dirt, and Coventry was at first forced to publish what became his most famous work anonymously. Despite which it made his name. The Angel in the House was a celebration of married love, an institution which Patmore, a deeply religious man, regarded with a religious awe. At first it was greeted with general indifference. But then it began to catch on, until in the 1880s his popularity rivalled Tennyson's - but unhappily, less for his poem's religious and philosophical depth than for the sentimental emotions which it inspired. Just as the public took to it, the critics turned against it. "The laureate of the tea-table" one called him "with his humdrum stories of girls that smell of bread and butter". Patmore celebrated man as achiever, woman as his sweetest of helpmates at home. He once defined love as "the mystic craving of the great to become the love-captive of the small, while the small has a corresponding thirst for the enthralment of the great". No prizes for guessing which of these roles was reserved for Coventry and which for the three Mrs Patmores. There's a portrait of Patmore by Sargent in the National Portrait Gallery, painted in 1894, two years before his death: a splendid

Patmore hated and despised the common people. "The year of the great crime /" he wrote of Disraeli's 1867 reform bill, "when the false English nobles and their Jew / by God demented, slew / The Trust they stood twice pledged to keep from wrong." His one consolation was that, since the working classes were drunk for most of the time, they would not succeed in exploiting the new political power they enjoyed. Out of envy or pique, he alienated or discarded his closest friends: Tennyson, Emerson, the Brownings, Rossetti. He developed a violent hatred, says Gosse, for "sentimental faddists, humanitarians, anti-tobacconists and teetotallers". A dispute with his landlord cost him his cherished house in Hastings, an eviction all the more galling since he was building a church just over the road. Patmore's mistake, perhaps, was that he lived too soon. Today, he would be constantly in demand, with a Sunday Times column, a why-oh-why slot in the Mail on Saturday, a TV chat show: with all the familiar rewards - more than enough to buy him his house at Hastings - which our society lavishes on possessors of reliably intemperate tongues. david.mckie@guardian.co.uk

|