Notre Dame Natasha

|

|

|

|

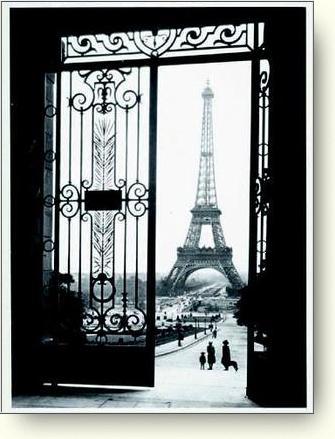

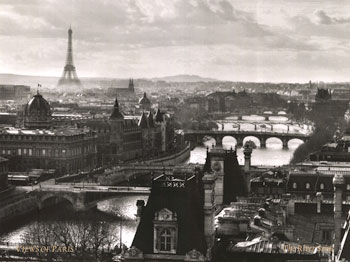

The Eiffel Tower was designed by the French engineer and bridge builder Alexandre Gustave Eiffel (1832-1923) for the Paris Exposition of 1889. The tower is 300 m (984 ft) high and consists of an open iron framework making it the highest manmade structure in the world at the time. It was the largest attraction at the Exposition and today it remains the most recognized structure in all of Europe. It was nearly

never built. After being awarded the contract to build the tower, Eiffel discovered that the Exposition Committee would only grant about a fourth of the monies needed to construct it. Eiffel himself would have to finance the balance. He struck a deal that would make him a very rich man. He agreed to independently find the funders for his tower but he wanted sole control of the tower and its profits for twenty years. They agreed. In a surprise to everyone, including Eiffel, the tower was paid off in the first year. The deal that Eiffle hammered out is probably what saved the tower from destruction. Many in the arts and civic leaders felt the tower was an abomination. "They have only erected the framework of this monument, It has no skin" The whole idea that iron -- just iron -- could be beautiful, flew in the face of architectural history. Everyone knew that the great cathedrals and palaces had all been built of stone with the careful craft of ornamentation which adorned them. Sure, iron can play a part in an unseen, underlying structure such had been done with the Statue of Liberty, but to leave it exposed was just poor taste. It was like showing your dirty laundry. A Committee

of Three Hundred was formed and they petitioned for its demise:

Honored compatriot, we come, writers, painters, sculptors, architects, passionate lovers of the beauty of Paris -- a beauty until now unspoiled -- to protest with all our might, with all our outrage, in the name of slighted French taste, in the name of threatened French art and history, against the erection, in the heart of our capital, of the useless and monstrous Eiffel Tower.It may have taken every bit of those twenty years to change some people's minds. All of the other iron buildings built for the Exposition were torn down shortly after (a shame). Today we look upon Eiffel's tower as anything but hideous. Mary Louis King calls it "a monument to nineteenth century architectural engineering and a frank display of structure and material." Although built of iron, it is an inherently inferior material and a single beam is unable to withstand large stresses. That is why the tower appears over engineered by today's standards. Though, from this very weakness its' simple beauty is found. If you look at the tower, the tight lattice work of beams sort of mimic the biological cellular structure of a plant. In 1855, Sir

Henry Bessmer discovered a process of converting iron into steel

thereby

making it much stronger and lighter, but the evolution from invention

to

practical use and mass production took many years. Steel would

eventually

replace iron and would bring the "sky scraper" to the city skylines of

America and in 1885 (actually four years prior to the Eiffel's tower),

William LeBaron Jenney built the Home Insurance Building in Chicago --

the first sky scraper. |

| Official

Eiffel Tower Web Site

Years

Built: 1887-1889 for

1889 Universal Exhibition and Centennial of the French Revolution

Number of

Iron Workers: 300 Height:

300.51 meters (986

feet) (+/- 15 cm depending on temperature) Steps to Top: 1789 (Birnbaum), 1671 (Joseph Harriss), 1652 (others)

|