|

|

|

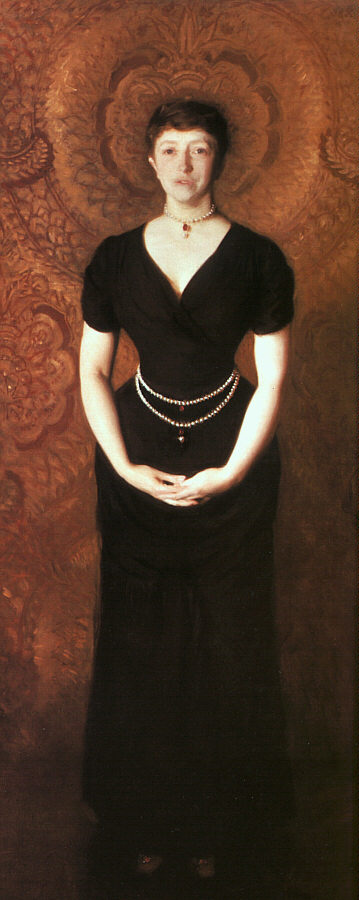

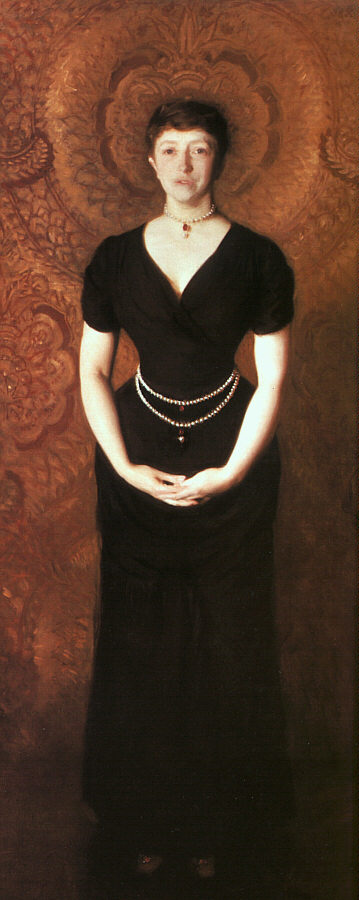

John Singer Sargent -- American painter 1888 Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston Oil on cavas 190 x 81.2 cm (74 3/4 x 32 in.) Jpg: Carol Gerten's Fine Art Much of the wealth of European art that American now has in its museums has a lot to do with a small handful of very farsighted and eccentric art collectors during the Gilded Age . Few of these were as eccentric and interesting as Isabella Stewart Gardner (1840-1925). She was born the daughter of David Stewart, a business owner from New York and Adelia Smith. She married a wealthy Boston financier John Lowell Gardner in 1860 at the age of twenty. Everyone called him Jack, and everyone called her Mrs. Jack. From her home in Boston which acted as the center of her own little solar system, she seemed to continually hold aloft a whole host of artists – musicians, writers, painters, all floating around her in various orbits. She had a bundle of energy and seemed to delight in ruffling the feathers of her fellow Bostonian socialites with her audaciousness. As fast as her husband brought in their huge fortune, she was just as determined to spend it on art, and by the time of her death had amassed an amazing collection that is now part of a museum which bears her name.

The first time Mrs. Jack met Sargent was in England in 1886 by introduction of Henry James. When he finally paints her two years later it would be on his first professional trip to America. The painting started in December of 1887 in Boston. For Sargent, it proved difficult. She was a restless sitter, given her high energy, she would continually look out the window to see what was happening on the river outside their home at 152 Beacon Street, Boston. Sargent grew frustrated and after eight unsuccessful attempts was willing to give the entire enterprise up but Mrs. Jack was reported to have insisted “ . . . as nine was Dante’s mystic number, they must make the ninth try a success" and it was (Morris Carter, 1925). Mrs. Jack loved the painting and thought it the best portrait John ever did, even tried to get Sargent to admit as much. Her husband, on the other hand, who was painted by Mancini, had an opinion altogether different and expressed it in a letter to his wife from New York: “It looks like hell, but looks like you.” A person's harshest critic can sometimes prove to be the most revealing. Though her husband didn’t have the sensitivity to appreciate, Sargent had pulled it off, and had captured the eccentricity and essence of Jack Gardner’s wife and he as much admits it.

When the painting was shown at the St. Botolph Club, Boston, it caused a bit of a stir. The décolletage and the flattering curves of her dress made her husband request that the painting never be exhibited in public again during his lifetime. Mrs. Jack honored his wishes and even refused repeated requests by Sargent to show it in other exhibitions until after her own death, but she clearly loved the painting. The friendship between John and Isabella would prove to be invaluable. With John’s orbit around her so tight patrons came streaming to his studio. With the exception of Stanford White (architect who connected John with the Boston Public Library) and Henry James (who lauded Sargent to the American public in the press and in England), there were few other friends who were as influential at opening doors for him. The friendship between the two was warmly felt, and it was through Sargent that Isabella was able to acquire some significant pieces for her museum. What made Isabella Stewart Gardner tick? When most benefactors were willing to give of their generous collections to distinguished institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York or even the Museum of Fine Art in Boston (which was just around the corner from her) she seemed to stand alone and with a singularity of purpose and determination of mind that I so greatly admire. She was her own woman and so indicative of the type of women around Sargent -- yet another strong woman. Some of the drive came from the loss of her infant son and the inability to have any others. In the vacuum of what she clearly wanted, it seems that artists would become her family.

By the time of her death, July 17, 1924, Mrs. Jack had collected twenty-two of his paintings, nine medallion and cartouche cast from the Boston Library work, and two sketchbooks. By Natasha

Wallace Anders Zorn

|