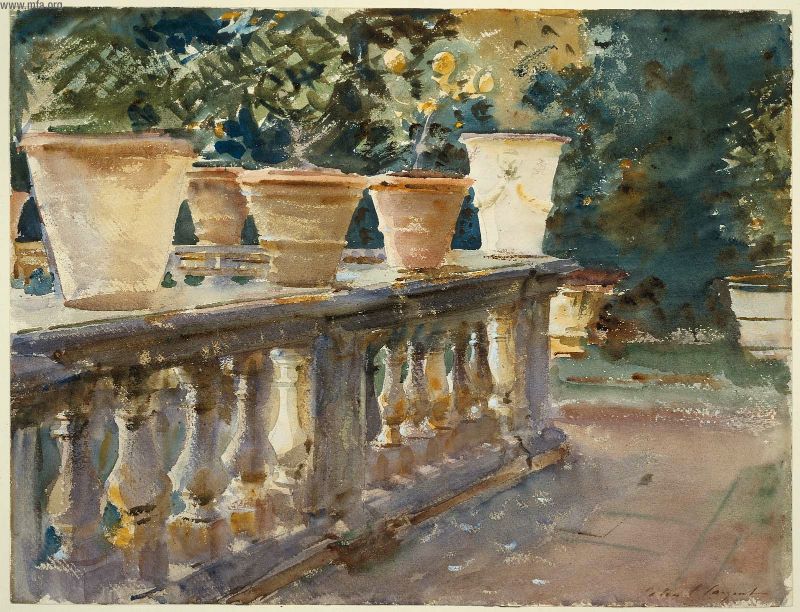

Villa

di Marlia, Lucca:

The Balustrade

John

Singer Sargent

-- American painter

1910

Museum

of Fine Arts,

Boston

Transparent

and opaque watercolor over graphite pencil, with wax resist on paper

40 x 52 cm (15 3/4 x 20 1/2 in.)

The Hayden Collection–Charles Henry Hayden

Fund

12.228

Jpeg MFA

(See

interactive zoom

at the MFA)

This was painted in

one of the villa

di Marlia near Lucca. He painted many like this in Tuscany and

around

Rome. He combines the elegance of the architecture with the

foliage  of

the garden -- the post and the balustrade actually occupying a greater

importance in this composition. of

the garden -- the post and the balustrade actually occupying a greater

importance in this composition.

This simplicity and

grandeur, cleanness

and harmony are fundamental elements which run throughout his creative

mind. A man now in his fifties, mature in his style, has never fully

left

his roots of his twenties and the classical formal training he received

at the Ecole

des Beaux-Arts which put strong importance upon the study of

classical

design -- Greek, Roman Antiquity and the Italian Renaissance.

Although

as a young man he never won the coveted Prix de Rome Contest -

the

prize to study in Rome and paint the Great Masters and architecture in

and around -- it was something he did on his own and throughout his

travels.

It was, for him, an exercise in creative dexterity which he would never

leave. These paintings are a constant vigilance at keeping his

faculties

sharp for observation of the world around him. Although

as a young man he never won the coveted Prix de Rome Contest -

the

prize to study in Rome and paint the Great Masters and architecture in

and around -- it was something he did on his own and throughout his

travels.

It was, for him, an exercise in creative dexterity which he would never

leave. These paintings are a constant vigilance at keeping his

faculties

sharp for observation of the world around him.

To the Italian

Renaissance architects,

gardens were a balance between "Art" (the  regular

form of intended controlled growth) and "Nature" (the

irregularity

of unplanned and undisturbed outgrowth); and the relationship between

human

thought and human effort. This balance was asserted in symmetry within

the entire site of buildings and gardens -- one was never wholly

separate

from the other. Transitions from interior to exterior were sometimes so

subtle a person might not know when they were leaving the house and

entering

the garden -- or leaving the garden and entering the regular

form of intended controlled growth) and "Nature" (the

irregularity

of unplanned and undisturbed outgrowth); and the relationship between

human

thought and human effort. This balance was asserted in symmetry within

the entire site of buildings and gardens -- one was never wholly

separate

from the other. Transitions from interior to exterior were sometimes so

subtle a person might not know when they were leaving the house and

entering

the garden -- or leaving the garden and entering the  house.

Architectural elements, such as a balustrade, in this case, were

carried

outwards and themes of the garden were carried within. These elements

and

themes, gradually lessened respectively as one

explored deeper until

you

would either find yourself at the outer bonds of unplanned nature or

within

the fully designed inner rooms of the home. [1] house.

Architectural elements, such as a balustrade, in this case, were

carried

outwards and themes of the garden were carried within. These elements

and

themes, gradually lessened respectively as one

explored deeper until

you

would either find yourself at the outer bonds of unplanned nature or

within

the fully designed inner rooms of the home. [1]

As

always, John was not painting in a vacuum. Although they were often

done

for his own pleasure, interest in Italian Renaissance gardens were at a

forefront of the public's eye. This is a subject matter he took up on

his

trips to that part of the world starting in 1900, and would grow in

importance

as interest in American Renaissance Movement grew. Formal arrangements

for gardens were becoming more desired to complement the buildings

of

architects such as Charles McKim and Richard

Moris Hunt. As

always, John was not painting in a vacuum. Although they were often

done

for his own pleasure, interest in Italian Renaissance gardens were at a

forefront of the public's eye. This is a subject matter he took up on

his

trips to that part of the world starting in 1900, and would grow in

importance

as interest in American Renaissance Movement grew. Formal arrangements

for gardens were becoming more desired to complement the buildings

of

architects such as Charles McKim and Richard

Moris Hunt.

Surprisingly

enough, up to Sargent's

time, the gardens of Italy were virtually unexplored by scholars. There

had been one serious study by two Frenchmen -- Percier and Fontaine

back

in 1824 [2], (never

really distributed

outside of France) but it didn't compare to the well photographed (for

that time) and documented treatise by two young Americans -- Charles A.

Platt and his younger brother William Platt in 1893. Charles published

their findings for Harper's Magazine in two installments that year and

then in a book called "Italian Gardens" the following year. [3]

By the turn of the

century, interest

in the City Beautiful Movement was reaching critical mass. Some of the

principle figures had come together in Washington D.C. for the

McMillian

Commission of 1901. Daniel H. Burnham, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. (who

was

carrying on in his father's footsteps), Charles Moore, Augustus

Saint-Gaudens, and Charles McKim (the latter two of the Boston

Public Library fame) all presented their ideas for a comprehensive

and inclusive formal design of Washington D.C.'s central mall which

brought

together a hitherto fragmented conglomerate of parks and structures.

They

embraced the Classical Renaissance idea that gardens and buildings

should

exist in a symmetrical harmony. In a sense, they were carrying forward

what had been done at the World

Columbian Exposition of 1893.

There

was an

awakening in the popular

public. The acclaimed Edith Wharton, whom had been sending back

travelogue

articles of her trips for magazines such as Century and Harper's, in

1904

published her own very successful book "Italian Villa and Their

Gardens"

illustrated by Maxfield Parrish [4].

By 1910, interest in the American Renaissance Movement had reached its

zenith, and probably best expressed by the palatial estates of James

Deering's Florida "Villa Vizcaya" and Harold

F.

McCormick with his wife Edith Rockefeller (daughter of John

D.'s) "Villa

Turicum" at Lake Forest, IL. which sat overlooking

Lake Michigan with begining designs started by Frank Lloyd Wright

but really brought to fruition by Charles A. Platt -- the very

same

Platt who had published his "Italian Gardens" in Harper's some

seventeen

years previous.

We had come full

circle.

None of this would

have escaped John's

brilliant cognitive mind. Many of these people were friends or

acquaintances.

The people paying for these colossal residences were the same who

begged

for portraits. The men of the City beautiful Movement were his friends,

and in many cases fellow alumni of the Ècole

des Beaux-Arts.

America had come a

long way since Richard

Moris Hunt's

mother asked if the country was even ready for the Arts. Artisans were

employed in an unprecedented level of involvement. Herman Mueller

designing

gorgeous ceramic tile mosaics, Tiffany turning out breathtaking stain

glass

and silver, Augustus

Saint-Gaudens, creating intricately cut stone sculptures and

interior

wood moldings and mantel pieces; Many of his friends from the Broadway

colony days were doing mural work for new classically designed

state

capital buildings, city halls, libraries, monumental train stations,

new

governor's mansions all over the country. Frank

Millet was active at the highest levels, coordinating efforts for

the World

Columbian Exposition, sitting on boards of major art institutions.

John, himself had risen to the highest levels in the Royal

Academy.

American artists

were taking the

best of what the history of western culture had to offered, bringing it

home, adapting it and making it their own, building upon a the rich

wealth

of ideas in a manner and fashion unseen since the Italian Renaissance.

The stars had

finally aligned in

the sky. Artists were working in harmony towards a totality of beauty

that

was a pure personification of Beaux-Arts ideals. The public had

awakened

to a dawning of a new age. Museums which didn't exist decades before

were

now bursting at the seams from growing collections. The future seemed

boundless.

Art and artists were going to save the world . . . Well,

something like that.

Sunday, June 28, 1914,

two shots

were fired, an Archduke was dead, and the world would never be the same

-- but that's for another story.

In 1910, we hadn't yet

reached that

ugliness. As John had done so many times in Venice,

he applied his incredible skill in watercolors to the most simple and

beautiful

of things. It was always the rhythm and harmony of light abreviatedly

expressed

in quick strokes. The glittering reflected sun breaking through under

the

gritty fingernail scratches of his paper's surface -- the

unadulterated

pulp brought back to the middle of a dried washed plane. Quick hatching

strokes -- this way and that to show the foliage of the plant.

Little

dabs of formless wet color -- here and there, built up through the

complexity

of a difficult medium where colors don't like to stay -- and suddenly

three

dimensional forms emerge with texture; the stone balustrade, cold and

hard;

he clay planters warming in the sun.

We will forever be

left baffed by

its execution. John Singer Sargent is a true Grand Master of a

chess-playing-artist.

Each stroke of his brush already conceived and understood in his mind

four

and five moves out. Emotionally, we understand the simplicity in an

instant.

It's checkmate! There is no doubt about it! But how the hell he got

there,

and how he knew when to stop will forever leave us jawdropped.

Notes:

Provenance

Purchased

from the artist through M. Knoedler, New York, April 4, 1912

1) Katherine F.

Benzel; The Room

in Context: Design Beyond Boundries;" 1998; McGraw-Hill; p

147)

2) Choix des plus

célébré

Maisona de Plaisance de Rome et ses Environs. Par Percier et Fontaine,

Paris, 1824

Translated

| Choices

of the more celibrated

Mansions and Palaces of Rome and its Vicinity, by Percier and

Fontaine,

Paris, 1824 |

3) Charles A.

Platt; Italian Gardens,

Harpers New Monthly Magazine; July and August of 1893, pp. 165-180

4) When Edith

Wharton published

her "Italian Villa and Their Gardens" in 1904, it was a pendent to her

first full book "The Decoration of Houses" (1897), written with

her architect friend, Ogden Codman. The two together argured strongly

for

neo-classical houses and away from victorian designs -- it became a

standard

in the field of American interior design. both books became quite

popular

|