|

The death of Mr. John S Sargent RA, which we announce with great regret on another page, has closed an epoch in English painting. For all his unfailing desire to learn and his constant freshness of spirit and method, this man of genius was the last supreme figure in a period in the history of English painting which is now past. His harsher critics said of him that he was of his age, not for all time. Admiration is not likely to be refused to his masterpieces at any future moment; but in spite of the individuality of his genius he belonged to his own age; and the passing of the great painter drives home the truth that the age which he so brilliantly and shrewdly depicted is now past. John Singer Sargent, by common consent the greatest portrait-painter of his age was American by birth, but English by virtue of long residence. His father was Doctor Fitzwilliam Sargent of Boston, a descendant of William Sargent of Gloucester, England, who emigrated to Massachusetts before 1650. His mother had been Miss Mary Newbold Singer, a member of an old Philadelphia family. The accident of his birth in Florence on January 12th, 1856 has often been referred to as in a manner prophetic, so appropriate it seemed that a great painter should see the light in the capital of art, and that an artist of truly cosmopolitan outlook should be born far beyond the boundaries of his parents’ home in New England. His youth was spent in Europe. No stories of infant precocity are told of him, but we know that he rapidly acquired mastery in drawing and painting, to which he early devoted himself. He studied first in the Florence Academy of Fine Art, and at the decisive moment went to Paris, to put himself under Carolus Duran. Cheered by the encouragement and guided by the technical skill of this admirable painter, young Sargent soon reached the level of high perfection shown in the portrait which he inscribed “A Mon Cher Maitre Carolus Duran 1877.” At once spontaneous in design and mature in workmanship, this portrait met with immense success-helped we can readily believe, by the personality of the big and genial painter, just 21 years old. But it was not his first work; indeed he had already visited America in 1876 and become known as a painter of great promise. In 1879 he paid his first visit to Spain, where the country, the blazing sunlight, and the pictures of Velasquez combined to inspire the most famous of his early pictures the full length portrait of a Spanish dancer “Carmeneita” now in the Luxembourg. The picture, suggested by Spain, took form in Paris, where Sargent had a studio from about 1880 to 1884, when he definitely made London his home, settling in Chelsea (Sargent’s house was in Tite Street and was to remain his home for the rest of his life), near his fellow-American and fellow-artist Whistler. What the two men thought of each other is not recorded; but one is at liberty to presume that the little “Gadfly of genius,” while he may have admired, did not like his rival’s instant success, and that Sargent, the most unselfish of men, smiled and passed on. PORTRAIT PAINTING Many, but not all of Sargent’s clients in the early eighties were Americans, wealthy men and handsome women clamouring to be painted by the Boston man who had conquered Paris. Perhaps the chief picture of that date was "The Children of Edward Darley Boit” a well-known Boston man, a large canvas portraying with delightful simplicity four little girls in black frocks and white pinafores in a large nursery. Other American portraits to name a few out of many, covering some twenty-five years are those of President Roosevelt, and Mr. H B Marquand,; of Mrs. Endicott an elderly lady with an expression of great dignity and calm; of the beautiful actress Ada Rehan; and of three ladies who married eminent Englishmen - Mrs. Joseph Chamberlain (Mary Chamberlain 1864-1957 nee Endicott of Massachusetts), Miss Leiter, and Lady Randolph Churchill (nee Jenny Jerome of New York, mother, and a very bad one at that, of Sir Winston Churchill). In 1899 an exhibition of his works was held in Boston. It included 120 pictures, of which some 50 were portraits, and the interest of the collection, which drew visitors from all over the United States, and fixed Sargent’s reputation in his parents’ country at a very high level, was enhanced by his mural paintings in the Sargent Hall of the Boston Public Library. These famous paintings-famous alike for their merit and the violent opposition which they have aroused from more than one religious body, represent, in the painter’s own words, “ a pageant of religion-a mural decoration illustrating certain stages of Jewish and Christian history.” But after the artist settled in London (he was elected ARA in 1894 and RA in 1897), it was in the London galleries that, during the remainder of the 80s and down to about 1910, the public first saw his works. They form a long and noble series, marvelous in their vitality, but direct and free, dazzling in their textures, and for the most part vividly true as likenesses. Take for example the portrait of the late Lord Weymyss [n/a], the delightful aristocratic optimist, or by way of extreme contrast that of Asher Wertheimer, the great Bond-street art dealer. We should be inclined to rank “Wertheimer” the highest among all Sargent’s portraits of men, the grasp of character is so complete. But there are also for example the “Coventry Patmore” and the “Henry James.” The figure of the poet is one of command. He had attained to dogmatic certainty; if others do not share it so much the worse for them! But to Henry James certainty is no such simple matter; it can only be seen through hundred facets of a cut diamond, and the man of letters sits there, mentally turning the diamond, so to speak, till he gets the gleam of which he is in search. Sargent was always eagerly sought after by fair ladies in those days, for to be painted by him soon came to be recognised as a mark of distinction. Nobody wants to see a lady’s character analysed quite so mercilessly as this fine painter analysed his men. But if Sargent’s faces of young women are treated rather more slightly than those of the other sex, they were wonderfully vivid, while the attitudes and their dresses were always amazing in their in their freedom and essential truth. The full length of the Duchess of Portland, (though like Lord the Ribblesdale of the National Gallery) it is too tall, is a picture which future generations will rank with the best Gainsboroughs. So with half-lengths such as the “Duchess of Connaught” (Princess Louise of Prussia 1860-1917, the wife of Prince Arthur 1850-1942 favourite son of Queen Victoria), and “Mrs Chamberlain”; so more with three or four magnificent groups in which Sargent, late in the century, brought back and filled with a much more real life type of art which had been dead since the days of Lawrence. “The Three Ladies Acheson,” and the Tennant-Elcho-Adeane group which was painted for Mr. Percy Wyndham, and more than one of the pictures of Mr. Wertheimer’s family are at once all marvels of decoration and vitally true. From about 1910 it was difficult to induce Sargent to paint portraits. He was quite rich enough for an unmarried man, why should he go on with work of which he was tired, and which bound him so much to other people, sometimes no doubt rather trying people? So he traveled, lived a good deal in Venice, and amused himself by painting rapid vigorous sketches of landscape, architecture, and incident. Many photographs of these are shown in the big folio volume of Sargent’s works which appeared with a preface by Mrs. Meynell. When the Great War came Sargent placed his services at the disposal of the Government. His terrible picture “Gassed,” was a chief feature of the Academy exhibition of 1920, and is now in the War Museum. THE MAN AND HIS ART In person Sargent was a tall man with a full face of sanguine complexion, dark hair, and strongly marked eyebrows. He gave the impression of great strength combined with great nervous sensibility. A friend of his student days with Carolus Duran described him as then a “very tall, rather silent youth,” who though rather shy, could “upon occasion express himself with astonishing decision.” These characteristics were preserved in maturity, and to casual acquaintances Mr. Sargent appeared silent and shy. Hating pretence and affectation, he was extremely generous in his encouragement of less successful artists whose work he admired, often taking the practical form of buying their pictures. He was a great reader, knowing French, Italian, Spanish, and some German, and an a enthusiastic musician, being a brilliant performer on the piano. In the biography of the late Edwin Austin A Abbey RA (1852-1911 another American domiciled in England), by Mr. E V Lucas, there is a letter from Abbey, dated September 28, 1885, on his first visit to the Cotswolds, which deserves quotation, not only as giving the genesis of one of Mr. Sargent’s most poetical pictures, but also throwing light upon his tastes, methods of work, and personal characteristics : We are all as busy as bees in Broadway. Sargent has been painting a great big picture in the garden of Bernard’s two little girls in white, lighting Chinese lanterns hung among rose trees and lilies. It is 7 ft by 5 ft, and as the effect lasts about 20 minutes per day-just after sunset-the picture does not get on very fast. We have lots of music-Sargent plays, and Miss Gertrude Griswold sings to us like an angel……..Sargent nearly killed himself at Pangbourne Weir. He dived off the same and struck a spike with his head, cutting a big gash at the top…….it was here that he saw the effect of the Chinese lanterns hung among the tress and the bed of lilies. The picture “Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose,” was bought for the nation by the Chantry Bequest Fund in 1887 and placed in the Tate Gallery. Abbey’s letter brings out clearly the dependence upon “the thing seen” which was at once the strength and the limitation of Mr. Sargent’s art. He had acute sensibility to the facts and effects of Nature. And an extraordinary power of recording them in characteristic terms of the media he was using; but, though his pictures are generally well composed, he was not remarkably alive to the purely aesthetic significance in form and colour of what he saw. He composed in facts rather than forms. In this respect, and allowing for individual genius, he may be said triumphantly to close a period, for it is unlikely that we will ever again have a great painter along the same lines. Painting has, in a sense, gone deeper, both as regards the facts of Nature, and the means of their representation, and the thing seen is exchanged for the thing felt by the whole organism, including the unconscious mind. This, however, is not to say that Mr. Sargent was insensible to poetry when it was inherent in the facts or the mood of Nature represented, as in the picture named above, or in the human personality, as in the extremely beautiful picture of his niece, “Marie Rose,” exhibited at the Academy in 1913. It might be claimed, too, that in his later works, particularly after the shock of the war, without greatly changing his methods, Sargent did respond to the time-spirit, restraining the effect of “immediacy” and suppressing his more obvious skill in execution, in the effort to allow more permanent values to shine through the facts. His portrait of “Sir Philip Sassoon,” exhibited in the Academy of 1924, is a case in point. Nor, though Mr. Sargent was not in the special sense a decorative painter, was he deficient in decorative ability. His work in the “Sargent Hall” of the Boston Public Library, including the coloured relief of "The Crucifixion,” shown in the Academy of1901, is proof to the contrary; and his much-criticized group of “Some General Officers of the Great War,” in the Academy of 1922, presented by Sir Abe Bailey to the National Portrait Gallery. Showed in its very restraint a much deeper understanding of the problems of wall-decoration than appeared on the surface. NATIONAL POSSESSIONS It is Sargent’s importance as summing up and closing a period which, apart from his individual powers, makes peculiarly appropriate the generous provision by Sir Joseph Duveen of a special room at the Tate Gallery to contain his works in the national possession. They will include, presumably, the nine “Wertheimer Portraits,” bequeathed by the late Mr. Asher Wertheimer and at present housed in the National Gallery; “Lord Ribblesdale” and “Miss Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth,” in the costume designed for Irving’s revival of the tragedy at the Lyceum and once in his possession, both presented to the nation by the late Sir Joseph Duveen; “Carnation, Lily, and Rose,” and a number of drawings. No account of Sargent would be complete without reference to his water-colours, appearing in the exhibition of the Royal Society of Painters in Water Colours of which he became a member in 1908-and elsewhere; broad and summary, producing the full illusion of Nature but kept by the medium from undue assistance on the facts. From the very nature of his powers Sargent was not the best in black and white, and a collection of his portrait drawings shown some years ago at the Grafton Galleries left a feeling of disappointment . Masterly in some respects, they had too much the effect of means to an end, and lacked the finality, as of something only existing in that form, which is the mark of a really good drawing. Sargent was honorary DCL of Oxford and honorary LLD of Cambridge, and an officer of the Legion of Honour; he was also a member of numerous British, American, and foreign artistic societies. He is also represented in all the principal galleries of the world-in the National Gallery of Ireland by a portrait of President Wilson, painted in 1917 at the request of the executors of the late Sir Hugh Lane, who, as the highest bidder bought the blank canvas in Christie’s Red Cross Sale of 1915, but did not live to chose the sitter; in the National Gallery of Modern Art, Rome by a portrait of “Antonio Mancini,” presented by Sargent in 1924; and in the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne by “Hospital at Granada.” His club was the Athenaeum, to which he was elected under rule 11 in 1898. Notes

|

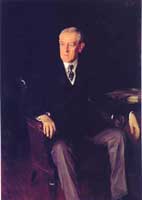

Dr. FitzWilliam Sargent 1886 (father to Sargent) |

Mrs FritzWilliam Sargent (nee Mary Newbold Singer) 1887 (mother to Sargent) |

Carolus-Duran

1879

La Carmencita

1890

Daughters of Edward Darley Boit

1882

General view of North End, Sargent Hall,

Boston Public Library

Coventry Patmore 1894 |

|

Henry James 1913 |

|

Winifred, Duches of Portland 1902 |

|

|

|

Acheson Sisters (Ladies Alexandra, Mary and Theo Acheson) 1902 |

Gassed

1918

Edwin Austin Abbey

c 1888-1889

Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose

1885-86

Rose-Marie Ormond

(later Madame Robert André-Michel)

1913

Sir Philip Sassoon

1923

Crucifixion (relief)

c 1899

Lord Ribblesdale 1902 |

Hospital at Granada 1912 |